Philadelphia Animal Specialty & Emergency

Author: Erik Zager, DVM, DACVECC (Critical Care Doctor)

The “acute abdomen” is a term for the syndrome that consists of sudden onset abdominal pain combined with any gastrointestinal signs such as vomiting, retching, diarrhea, anorexia, constipation, or nausea. The causes of the acute abdomen can range from mild conditions that can be managed medically on an outpatient basis, to ones that are life threatening and may require emergency surgery. Causes include: distension of a hollow viscus(e.g. stomach or intestines), distention of an organ capsule (e.g. spleen or kidney), traction (e.g. torsions), inflammation (e.g. pancreatitis or septic peritonitis), ischemia (e.g. thrombosis); miscellaneous (e.g. spinal pain, organ mineralization).

Certain historical findings can lead the clinician to suspect abdominal pain. These include head bowing, inappetence, lethargy, vocalization when touched, or reluctance to walk or jump. In addition to the classic gastrointestinal signs of vomiting, diarrhea, and inappetence, patients with an acute abdomen may also be presented due to owners noticing a distended abdomen, icterus, stranguria, vaginal discharge, or tenesmus. Once a general history is obtained from the owner, specific questions should be asked regarding dietary indiscretion, consumption of high-fat foods, previous heat cycle, previous surgeries, and any presence of polyuria or polydipsia.

There are some breed and age-related predispositions that are important to remember as well. Miniature Schnauzers and Yorkshire Terriers are overrepresented for pancreatitis. Older dogs are at higher risk for GDV and pyometras.

Physical examination is the most important part of the workup of the acute abdomen. As some of these patients can present unstable, examination should start with the ‘ABC’s of triage, which are airway, breathing, and circulation. This initial assessment should take less than 30 seconds. Following this initial evaluation, a full physical examination should be performed in a systematic manner, with special attention given to:

Volume status

A patient with hypovolemia may have tachycardia (sometimes bradycardia in cats), slow capillary refill time, poor pulse quality, weakness, or altered mentation.

Abdominal palpation

Attempt to localize the pain as much as possible, which can help guide further diagnostics towards specific organ systems

Rectal examination

Looking for hematochezia or melena. The prostate should be evaluated in intact males. The clinician should also press up on the sacrum to evaluate for sacral pain, and palpate the anal glands.

Spinal palpation

Spinal pain can mimic abdominal pain and should be evaluated on every acute abdomen.

Urogenital examination

A testicular examination and evaluation of the vulva for discharge should be performed on intact animals

Initial point of care diagnostics can be valuable in confirming the diagnosis of an acute abdomen and determining its cause. They can also be helpful for guiding initial therapy and stabilization if needed.

Blood pressure

Pain can result in elevated blood pressure, while hypovolemia or septic shock can result in low blood pressure.

Pulse Oximetry

Pain can result in tachypnea; however, vomiting can result in aspiration pneumonia, and tachypnea should prompt evaluation of oxygenation

Point of care ultrasound

The use of thoracic and abdominal focused ultrasound (TFAST, AFAST, VetBLUE) are used to evaluate for free abdominal fluid.

ECG

Evaluate for arrhythmias associated with many abdominal disease processes

Other useful tests

PCV/TS, blood gas analysis, blood glucose

The most important part of management of the acute abdomen is initial stabilization. This includes IV fluid therapy, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, pain control, antiemetics, and antibiotics in diseases with bacterial components.

AFTER stabilization efforts have been started additional diagnostics can be pursued to determine the cause of the acute abdomen syndrome.

Abdominal fluid analysis

If abdominal fluid is present, samples should be obtained either with ultrasound guidance, or using the 4-quadrant technique

Lactate and BG differential

If abdominal effusion lactate is >3mmol/L higher than serum, or if glucose of abdominal effusion is >20mg/dL lower than peripheral blood, then there is a high likelihood of septic peritonitis.

Potassium and creatinine

If creatinine is more than 2x higher than blood, or potassium is > 1.4x greater than blood, there is a high likelihood of uroabdomen

Imaging

Abdominal radiographs can be helpful for many causes of acute abdominal signs, but in other cases, abdominal ultrasound may be required.

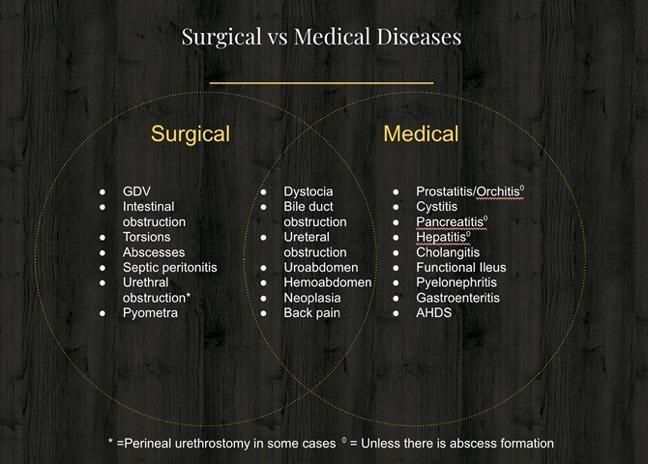

Treatment of the acute abdomen requires initial stabilization as described, as well as decisions about medical vs surgical definitive therapy.

For patients with a septic abdomen, early antibiotics are important. Pain medications should be given early, with full mu agonist opioids. NSAIDS must be avoided.

Treatment of arrhythmias typically involves correction electrolyte derangements, management of ischemia and hypovolemia, and pain control.

In summary, the acute abdomen should be treated rapidly on an emergency basis. Initial stabilization is paramount and should be followed by point of care diagnostic and imaging to determine the cause of signs. It is important not to rush diagnostics at the cost of stabilization.